Too much of a bad thing

Imagine, for a moment, that you’re an alien who’s been invited to Planet Earth to observe humanity. During a tour showcasing our species’ greatest achievements (the pyramids, deep-dish pizza, and so on), you are finally shown to a room with a computer.

The machine, you are told, is connected to something called The Internet, a magical world containing everything you could possibly want to read, see, or hear. Most impressively, you can easily find information on anything that’s happened in the news, anywhere in the world, at any time.

But after spending a few hours exploring, you begin to feel confused: Why do so many different parts of the Internet publish nearly identical content on the exact same topic, and at the exact same time? Why do dozens of separate web sites all post exactly the same YouTube video of yesterday’s late-night show, when it’s already easily available on YouTube itself? Why do the stories so often fail to live up to the headlines, and why is the editing so atrocious? Why are there web sites like this?

These are some of the oddities to which we human beings have become immune in recent years. And the answer to all of the above questions, of course, is advertising revenue. But it’s worth remembering that there is no practical benefit to consumers for dozens of web sites to post minute variations on the same exact story. There is no practical benefit to consumers for news organizations to embed videos produced by other media companies into their own CMSes en masse, accompanied by a brief recap. There is no practical reason that any readers should expect to put up with atrocious copy-editing and subpar thematic editing.

And yet we live with all of these things, over and over. We hardly even notice them anymore, except to make impotent jokes about the ubiquity of clickbait or the ‘John Oliver Video Sweepstakes.’ The Internet has transformed virtually every aspect of how journalism is conceived, designed, and produced, but we seem to obsess the most over how it is (or isn’t) monetized. We fret about declining ad rates and the rise of ad-blocking, but we pay virtually no attention to how the content being subsidized by those ads has itself changed.

And it’s changed, in many places, for the worse. Take a gander around the virtual metropolis of American journalism and you’ll find yourself surrounded by crappy rewrites of articles written far better by The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times. And even these paragons of journalistic virtue succumb to the page-view scrum on occasion. The Times recently announced an ‘Express Team’ that covers breaking news events on a rapid-fire basis, sounding not terribly different from content-mill generators like The Daily Beast or The Huffington Post:

According to the memo, the Times recently has been experimenting with a bigger rewrite team dedicated to “covering the web’s most compelling and fast-moving stories.” LaForge’s appointment is part of an effort to “take over and enlarge this initiative.”

Rather than eschewing aggregation, the Times seems to be moving to ensure that it can keep pace with fast-moving competitors, without sacrificing the paper’s commitment to high-quality journalism and accuracy.

Now, given that this is the Times, the content is still more compelling, better-edited, and more substantial than the lighter fare peddled elsewhere. It also has the express purpose of creating new subscribers, an objective that doesn’t even have a counterpart at most ad-supported news sites. And finally, there is some value in centralizing information across a broad array of topics within one trusted organization, so readers don’t have to visit five different sites to catch up on all the day’s news.

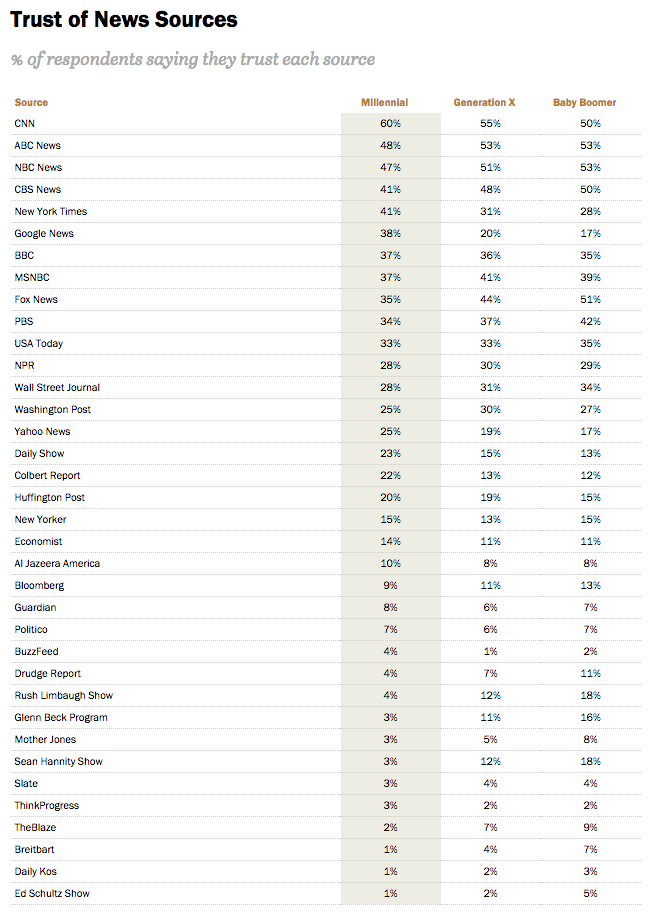

There was a word once for this sort of trusted organization: it was called a newspaper. And perhaps unsurprisingly, it is these legacy organizations – newspapers and long-running TV news programs – that have maintained the most reader trust in the Internet age (even among the youngest audiences!), despite the presence of dozens or hundreds of aggregators, furiously spinning out rewrites of others’ content by the minute.

Most coverage of journalism’s woes focuses on the advertising crunch: it’s becoming ever harder to monetize news content, because advertising CPMs (cost per thousand views) are decreasing in the face of virtually infinite supply. This is nearly universally decried as a terrible development for journalism, but it needn’t be.

Historically, advertising has always comprised somewhere between 1% and 1.5% of our national economy, a ratio that has changed little over time. In other words, the demand for ad space is relatively constant: it’s the supply that’s gone haywire. But instead of recognizing the long-term infeasibility of supporting hundreds of content producers with the same share of national spending that used to support a tiny fraction of that number, news sites have exerted an enormous amount of energy attempting to bite into each other’s rapidly diminishing shares of page views. In the end, the legacy organizations are seeing their revenues suffer due to the incursion of the zombie rewriting corps, while the aggregators themselves pay their writers barely enough to live on. All of these factors coalesce to produce headlines like this:

Strangely enough, none of these developments has stopped huge media conglomerates and venture capitalists from investing heavily in these very aggregation-centric properties, from Axel Springer’s purchase of Business Insider to NBC Universal’s investment in both Vox Media and BuzzFeed, and many other examples besides. One way of reading this is that legacy media companies are making smart plays for the upwardly mobile millennial set and gaining innovative ad tech in the process.

But another possibility is that, in the mad dash to capture The Next Big Thing in media, buyers are wildly overpaying. As Re/Code’s Peter Kafka reported in September:

Today’s transaction appears to link the FT and BI: Industry executives think Springer’s inability to land the Financial Times made them that much hungrier to get Business Insider.

They also believe the failed deal helped Springer justify Business Insider’s price, which values the company at around 9x its projected revenue for this year; in a conference call after the deal was announced, Springer executives said the $390 million value will be about 6x the company’s 2016 revenues. Another complementary theory popular with media executives I’ve talked to in the last week: Springer wanted a digital asset, and even at a rich price, Business Insider was more affordable than publishers like BuzzFeed and Vox Media, which owns this website.

If this latter theory holds water, it would mark a doubling down on a failed business model. Very few, if any, sites have managed to support a substantial journalistic operation via digital ad revenues alone. This leaves us with two distinct models: large, legacy organizations with complementary revenue sources (subscriptions for newspapers or TV advertising for major news channels) on the one hand, and aggregators relying purely on online ad revenue on the other. (There are also niche sites produced as works of love, business models be damned.)

Both ad-blocking and the possibility of an eventual contraction of available VC money threaten to severely damage the latter business model. They certainly won’t damage advertisers, at least not significantly: they’re going to find a way to spend their budgets one way or another. But, and this should be clear by this point, they also won’t necessarily damage journalism. At the Times, for example, the CEO and executive editor are clearly focusing on building out subscribers, not simply inflating their page views. And at The Economist, deputy editor Tom Standage summed up the magazine’s long-term approach:

Ultimately, I think what’s interesting about the current environment is that there is an awful amount of froth around. There are an awful lot of news organizations that are being funded with VC money, and the VCs have persuaded themselves that because the news organizations use software, they’re a bit like tech companies and can be valued like tech companies. I don’t think it’s true, and I think an awful lot of these companies seem to have business models that are dependent on advertising, and I don’t think it’s going to work. So I think there’s going to be a shakeout.

…

The Economist has taken the view that advertising is nice, and we’ll certainly take money where we can get it, but we’re pretty much expecting it to go away.

High-quality content producers, in other words, are reasonably confident that they can continue to extract monetary value from their readers even if and when the advertising landscape shifts dramatically. If, however, you’re a ViralNova, EliteDaily, Upworthy, Huffington Post, or another outfit with similarly vanishing per-article revenues, you’ve got to be worried. And you should be, because much of your content is terrible.

But that doesn’t mean any of us should be overly concerned if some of these businesses begin to go under. If anything, the eventual constriction of ad inventory supply could help return CPMs to financially sustainable levels. Better yet, it would help consolidate ad revenue among truly valuable journalistic institutions that could really use the incremental revenue to invest in ambitious projects. (Like this, for example.)

The future of any particular news organization may be in doubt. But the future of journalism in general is still quite strong, and neither ad-blocking nor the collapse of aggregators changes that.