Facebook on trial in Europe

One of the primary reasons for joining [Facebook] is the fact that “everyone is on it”.

- ‘From social media service to advertising network: A critical analysis of Facebook’s Revised Policies and Terms’, DRAFT March 31, 2015, p. 13

An unfortunate series of events

Once again an American tech behemoth is in trouble in Europe.

This time it’s Facebook’s turn. On Monday, Belgium’s Commission for the Protection of Privacy (CPVP, for Commission de la protection de la vie privée, or the ‘privacy commission’) announced a bold move in its ongoing battle with the social network:

Belgium’s data-protection watchdog said Monday that it is suing the California-based social media firm over its privacy practices, a sharp escalation in a set of probes across five European Union member states.

At the same time, the EU’s 28 member states approved a draft of a long-debated pan-European law that would boost the same national regulators’ powers over companies like Facebook.

The lawsuit, which opened with an initial court date on Thursday, is the culmination of a series of tit-for-tat tussles between Belgium’s data privacy regulators and Facebook, which – apart from maintaining its innocence – continues to insist ‘that it should only have to answer to the regulator in Ireland, where its European headquarters are based.’

In many ways, Facebook’s problem is similar to Google’s, in that the two firms continue to run afoul of European privacy norms (which are generally far stricter than their rather laissez-faire American counterparts). Ever since the European Parliament and European Council passed a landmark data protection directive in 1995, American and European policies on the collection of user data have diverged pretty dramatically.

More recently, this year has seen a series of speed bumps for Facebook in Belgium. First, a February report written by academics at the Catholic University of Leuven and the Free University of Brussels at the request of the Belgian privacy commission broadly criticized Facebook privacy policies and found that the company’s ‘opt-out approach for behavioural profiling and social advertising does not meet the requirements for legally effective consent.’

Facebook responded with a blog post, arguing that the scholars’ report ‘gets it wrong multiple times in asserting how Facebook uses information to provide our service to more than a billion people around the world.’ The post disputed several of the report’s claims but conceded that ‘the researchers did find a bug that may have sent cookies to some people when they weren’t on Facebook. This was not our intention – a fix for this is already under way.’

Then, last month, the CPVP raised the stakes with a report of its own, specifically tailored to the matter of ‘social plugins.’ Facebook’s Like and Share buttons form the crux of the report: Belgian authorities argue that these buttons, which are embedded on countless pages and sites – in other words, not just on Facebook’s own site or mobile app – are sneakily collecting user data across the Internet, even when the user doesn’t have a Facebook account and never clicks on the button.

What exactly is being collected?

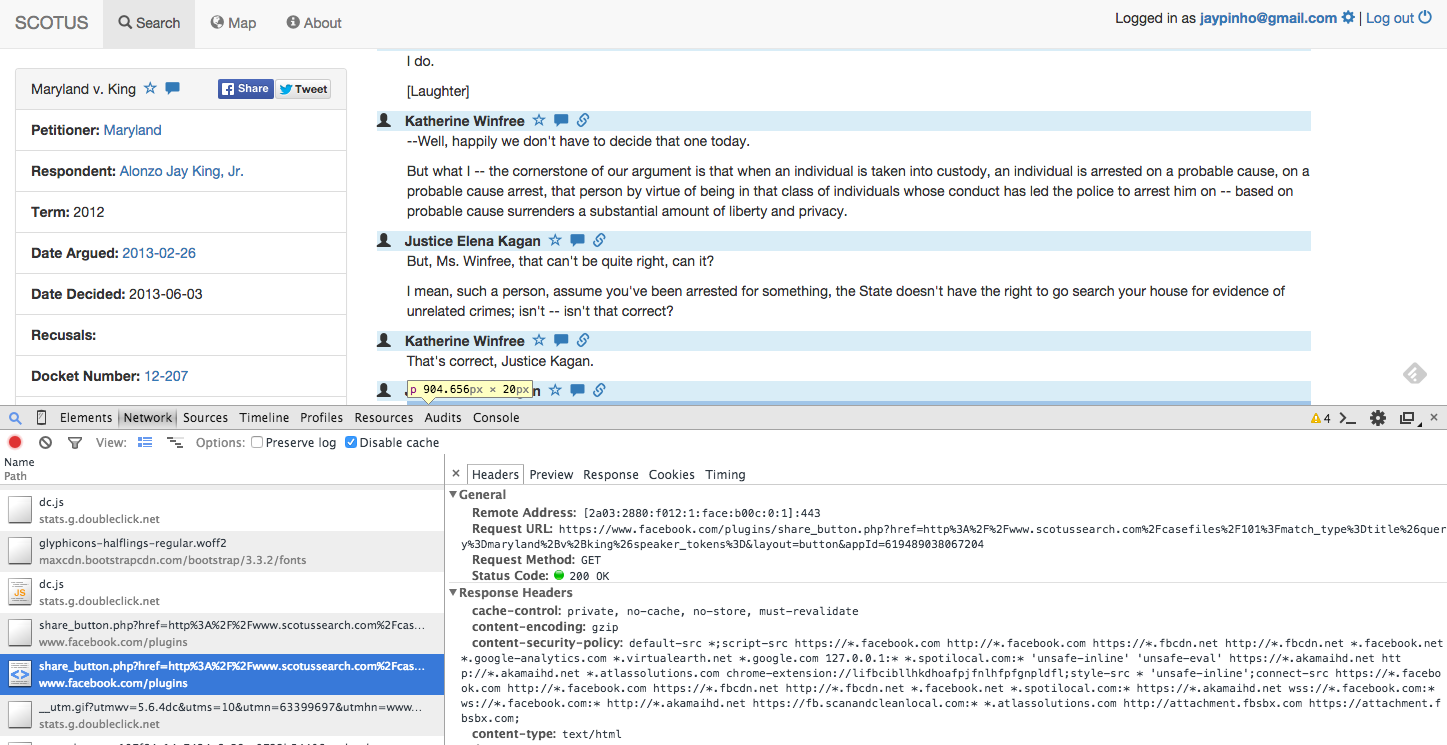

That data collection is taking place on the page load, and not just on a click event, is undeniably true. Take my SCOTUS Search site, for example. Every oral argument page contains a Facebook Share button (seen in the top-left corner of the below screenshot), which sends page URL data to Facebook as soon as the button loads:

If you look closely at the ‘Request URL’ section of the above screenshot, you can see that the full URL is being sent in encoded form to Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/plugins/share_button.php?href=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.scotussearch.com%2Fcasefiles%2F101%3Fmatch_type%3Dtitle%26query%3Dmaryland%2Bv%2Bking%26speaker_tokens%3D&layout=button&appId=619489038067204

In other words, as soon as I visited that page, even though I never clicked on the Share button, the address of that page was sent to Facebook anyway. And since I’ve logged into my Facebook account recently, Facebook is capable of associating my actual name – Jay Pinho – with the page I just visited, even though I’m not on Facebook right now and I never even clicked on Share.

You can see why this would upset the general public, not just regulators. Facebook Like and Share buttons are all over the place (including on 32% of the top 10,000 most popular web sites, according to page 16 of the CPVP report), so there’s virtually no limit on how extensive Facebook’s record of your browsing history is. That tends to scare people. It certainly scares Belgian regulators.

The Belgian privacy commission’s report

As mentioned previously, Facebook insists that only Ireland, the seat of the company’s European operations, has the jurisdiction to regulate its activities affecting anyone in the European Union. Belgium’s privacy commission, therefore, dedicated the first 16 pages of its 28-page report to rebutting this claim.

I won’t get into the technical details of that particular dispute, which is both beyond my expertise and profoundly boring. But starting on page 16, the report delves into the details of its complaint against Facebook.

In no particular order, the report’s authors emphasized the following:

-

Lack of anonymity: Facebook’s tracking is particularly noteworthy because it ties user browsing data to personally identifiable information (PII) that it possesses due to its role as a social network. Unlike other data brokers, whose collection and transfer of data remains fully anonymous, Facebook is easily able to match a user’s real name and other private data to his or her browsing history.

-

Neither deletion nor anonymization of data satisfies Facebook’s Belgian legal obligations: The Belgian Privacy Act of 1992 regulates the ‘processing of personal data,’ not just its collection or even permanent storage. Therefore, the privacy violations caused by Facebook’s collection of data via social sharing buttons are not mitigated by the data’s eventual deletion or anonymization.

-

Facebook cannot reasonably claim that such data collection is necessary: Article 5 of Belgium’s Privacy Act grants firms the right to process personal data in several scenarios, including when a) the user consents unambiguously or b) such data processing is necessary to fulfill a contract between the firm and the user. (See pages 11-12 of this privacy commission document for a helpful explanation.)

The CPVP then cleverly divides Internet users into two camps: those who don’t use Facebook and those who do. For the former group, the CPVP explains that Facebook data collection via social sharing buttons is clearly unnecessary for contractual purposes, since those Internet users don’t even have Facebook accounts. And as for the latter, the CPVP argues, the very fact that Facebook has an opt-out provision underscores the optionality of the data collection: ‘The possibility they are given…by Facebook to block or refuse the use of the cookies is sufficient to ascertain the non-necessary nature of this use for the performance of the contract for signing up to Facebook.’

(On first glance, this line of reasoning doesn’t entirely hold up. Taken to its logical extreme, if every Facebook user opted out of targeting, the company would likely go bankrupt: advertising sales constitute 94% of its total revenue. So it’s not that targeting itself is unnecessary: it’s that Facebook has made the calculation that allowing customers the option to opt out won’t significantly impact its bottom line. Of course, it is certainly debatable whether such functionality is sufficient, but that doesn’t justify penalizing firms for their own [albeit timid] attempts at setting minimal privacy standards.)

-

Users are not unambiguously consenting, either: Without being able to satisfy Belgian regulators that data processing is necessary to fulfill a contract, Facebook must rely on Article 5’s option A: ‘The data subject has unambiguously given his consent.’ In 2011, an EU Data Protection Working Party document (p. 35) defined the elements of valid consent as ‘freely given,’ ‘specific,’ ‘informed,’ and ‘unambiguous.’

Belgium argues that Facebook violates the ‘freely given’ standard in two ways:- Facebook occupies the ‘dominant position on the market of social networks. One of the most important reasons to register on Facebook is exactly because “everybody is already on Facebook”.’

- Users cannot meaingfully choose what data processing they will allow. ‘It is not possible, for example, to only grant consent for Facebook’s basic functions (e.g. sharing information with your friends), without also granting consent to the processing of your data for commercial profiling.’

The CPVP also argued that users’ consent was neither ‘specific’ (because there are not granular controls over what data to allow) nor ‘informed,’ especially following a European Court of Justice ruling that ‘purely offering a hyperlink (which does not oblige users to read the entire text) is insufficient.’

But the Belgian regulators press on. ‘Unambiguous’ consent is not present either, they claim, because an opt-out function is insufficient (again, according to that same 2011 document).

While the above is not an exhaustive list of the privacy commission’s complaints about Facebook’s data collection practices, it captures the most glaring violations in the eyes of the regulators. Towards the end, the report lays out several recommendations for the regulation of social share buttons, including:

- Transparency: Facebook ‘must provide full transparency about the use of cookies,’ meaning that both their content and purpose must be disclosed in an updated and easily available fashion.

- Data collection limitations: Unless it obtains unambiguous consent, Facebook should stop the routine creation of long-term ‘unique identifier cookies’ of non-Facebook users and even of Facebook users for whom such collection is unnecessary for ‘a service explicitly requested by the user.’ Facebook should only use session cookies for collecting data from social plugins for personalization, not regular cookies. And a social plugin should also not collect data simply when it is loaded on a page: it should only transmit data to Facebook when the user engages with the plugin. As a positive example, the commission cites the ‘Social Share Privacy’ plugin, a tool that some sites have begun using in order to obtain their visitors’ consent before sharing data with social networks.

- End users should get tech-savvy: The privacy commission lists several examples of browser extensions that block tracking: Privacy Badger, Ghostery, and Disconnect.

Unfortunately, one of the report’s final recommendations was misleading:

Internet users can also protect themselves by using the incognito or “private navigation” mode offered as a functionality in recent versions of most frequently-used browsers (Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, Safari, etc.). This functionality forces the browser to delete traces of surfing behaviour (cookies, history, etc.) after the window is closed and thus protects Internet users from being tracked by Facebook or others.

This is not precisely true. While incognito mode does prevent certain types of tracking (persistent cookies, for example), it does not technically ‘[protect] Internet users from being tracked by Facebook or others.’ Indeed, in a test I conducted just now, I opened a Chrome incognito window and searched for a term on my own site, SCOTUS Search. The site’s database saved my IP address, timestamp, and query data, despite the fact that I was operating in incognito mode. Indeed, even Google itself saves your search history in incognito mode if you’re logged in at the time.

The distinction is a crucial one: Google Chrome is a browser, and therefore can stop tracking users as a browser. But that doesn’t necessarily prevent any of the web sites a user is visiting – to say nothing of the Internet Service Provider – from logging the page URLs (or whatever else) and tying that back to an IP address. Moreover, if that same user, on the same IP address, then re-visits those pages later on while not in incognito mode, the site is technically able to tie all that user’s incognito activity to everything else it already knows about what the user did while not in incognito mode. This sort of defeats the purpose.

Where does this leave Facebook?

The answer is not entirely clear. For one thing, the issue of jurisdiction has yet to be settled: Facebook insists that it should only be regulated by Ireland and that, therefore, the Belgian commission’s findings are irrelevant. And indeed, in recent days national European regulators have taken especially aggressive stances against American tech firms: just last week The New York Times reported that France’s privacy regulator (CNIL, for Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés) is demanding that Google apply ‘the right to be forgotten’ – functionality mandated by the European Court of Justice allowing users to request search results about them to be taken down – to all of its domains worldwide, not just in Europe.

Further complicating matters is the step taken by the European Council on Monday. The draft of a new data protection bill, to replace the 20-year-old one currently in effect, was approved which would (with some limitations) enable an individual European country’s national regulator – a so-called ‘one-stop shop’ – to take the lead in pursuing action against an offending company. This could cut both ways for multinationals like Facebook and Google: on the one hand, avoiding a convoluted mishmash of 28 unique national privacy regimes across the EU is a good thing. On the other hand, as the Wall Street Journal article underlined, ‘the fact that one national regulator in Belgium—with about 2% of the EU’s population—could force Facebook into court, underscored some tech companies’ worries about the provision.’

There is, furthermore, an omnipresent suspicion in American circles that the EU’s assertive regulation of American tech companies is indicative of protectionism rather than a genuine interest in user privacy. Nationalist objectives are likely a factor to some extent, but the evidence for this theory is not as clear as that for the more straightforward explanation, which is that Europeans value their digital privacy more than Americans do, for reasons ranging from the historical to the cultural. How this divergence will affect the foreign operations of Facebook has yet to be determined.