Video is not your savior

The other day I was emailing a friend of mine about some ideas for a joint podcast. In his response, he briefly mentioned:

Btw if we REALLY want to be on the edge, i think the future is video.

He’s not the only one: virtually everyone in media and advertising has been saying the same thing. Perhaps the most prominent recent example: Facebook’s vice president for Europe, Nicola Mendelsohn, predicted last week that in five years Facebook will be ‘probably all video…If I was having a bet, I would say: video, video, video.’

News organizations have come to the same conclusion. Here’s The Information last month on Mashable:

The video push, which involved hiring new personnel and buying equipment, sent Mashable’s costs soaring to between $4 million and $5 million a month, according to a person familiar with its figures. Those costs were significantly higher than its annual revenue that last year reached about $40 million. In other words, Mashable was at times burning through more than $1 million a month in cash.

Here’s Nieman Lab last month on BuzzFeed:

BuzzFeed has made a huge commitment to building out its video capabilities, and funny and shareable videos have become its staples. The company launched BuzzFeed Motion Pictures in 2014. It now publishes 65 original videos each week, and earlier this year BuzzFeed CEO Jonah Peretti moved to Los Angeles, where BuzzFeed’s video operations are based. The company says it has more than 7 billion content views per month, with video counting for a majority of them across all platforms.

Here’s Nieman Lab in April on Vox.com:

“It’s always been our intention with the video team to build audience and then monetize,” Klein said. “There are huge business and audience reach opportunities.”

And here’s Politico in March on The New York Times and virtual reality:

At the same time, as the industry is starting to see a critical mass of publishers investing in VR, the Times appears to be emerging as something of a standard-bearer for the medium’s journalistic and financial potential.

“The prize for us as a company, it’s about, can we get right out there on the edge of what’s possible,” [New York Times CEO Mark] Thompson told POLITICO at Friday’s party. “It’s one of the most exciting things, one of the most buzzy things we’ve done.”

You get the picture, from these and countless similar pieces: video, with its high CPMs (often several multiples higher than display ad rates), has become the assumed savior of journalism. Advertising budgets will continue to migrate from TV to online video, and all will be well with the world.

Not so fast.

First, very likely nothing will ‘save’ the news media. There are long-term trends that all point to the decline of news as a major force in business, some of which could be reversed but – for a variety of causes, most notably the tragedy of the commons effect – probably won’t be, at least not for some time. Perhaps a new advertising model will help, but at this point I’m skeptical about many of the promises. The fundamentals haven’t changed from where they’ve been for years: there’s far too much news content to sustainably absorb the relatively constant advertising budgets. Either the supply of content has to drop or the demand for ads has to increase, and the latter is extremely unlikely given its historical flatness.

Second, the headlong rush into video mirrors the way many (although not all) publishers approached Facebook’s Instant Articles announcement just over a year ago. It would be the future, the savior even. The Washington Post has been syndicating all of its stories on Instant Articles since last September.

There’s nothing wrong with Instant Articles: indeed, it’s a wonderful product from a consumer standpoint. (Not to mention from Facebook’s, as you will soon see.) But too many publishers got caught up in short-term magical thinking: after Facebook launched the product with nine initial publishing partners, the lucky few (along with their peers who joined later) predictably reported fantastic engagement, higher time spent on articles, and strong revenue.

Why was that happening? Well, because when there are only ten or one hundred or even one thousand publishers using Instant Articles and no one else is, their articles automatically look faster and cleaner by comparison. Not to mention it’s highly likely Facebook helped out: Instant Articles was an important part of Facebook’s long-term strategy to ensure that all content stays on Facebook, so they’re incentivized to promote it. Any given publication’s Instant Article was thus quite likely to be featured prominently on thousands of users’ news feeds at the start.

But look a little further into the future: eventually, most major news organizations will publish much of their content on Instant Articles. (Indeed, Facebook just opened up the platform to all publishers a mere two months ago.) At that point, there will no longer be a meaningful comparative advantage since everyone else will be on it too, thus enjoying the same page speed and design lift. Facebook won’t be able, nor have any incentive, to promote a particular organization’s Instant Articles because, instead of ten or twenty publishers to promote, they’ll now have 100,000.

Question: In such a world, what are the chances any single news organization’s stories will stand out?

Answer: Roughly the same chances as before Instant Articles existed – except now they’re also forking over 30% of their ad take to Facebook (unless they sell direct). In short, for the cost of building out storage and a few servers to host all that new content, Facebook gained access to news organizations’ output as well as a cut of their ad revenue. (They’re smart, those guys.) It is unclear what news organizations received in return.

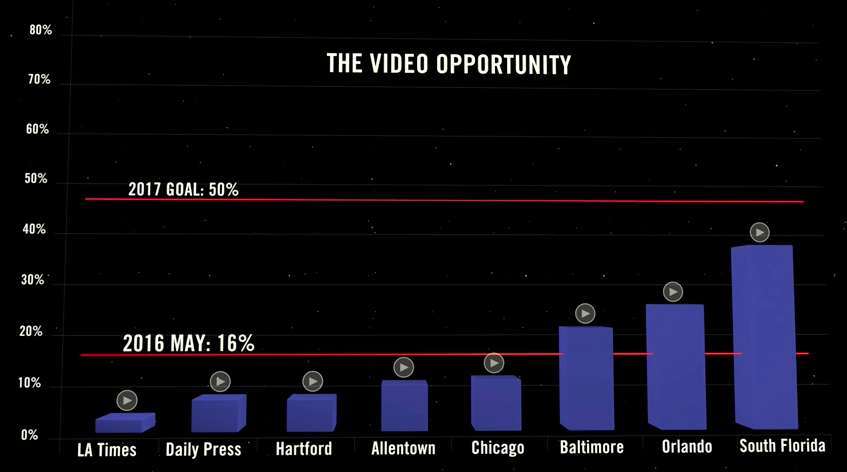

This scenario applies equally to video. Why is video so hot right now? Because – unlike display inventory – its supply is relatively scarce, so its CPMs are sky-high. You can probably guess where this is going:

Tribune Publishing — now known as ‘tronc’ — chairman Michael Ferro appeared on CNBC today to announce some of his plans to revitalize the company whose share price has dropped by nearly half in just a couple years. Part of this plan, it seems, is to start churning out mass-produced videos without much need for human assistance.

“There’s all these really new, fun features we’re going to be able to do with artificial intelligence and content to make videos faster,” Ferro told interviewer Andrew Ross Sorkin. “Right now, we’re doing a couple hundred videos a day; we think we should be doing 2,000 videos a day.”

For context, BuzzFeed does around 65 to 75 videos a week.

(Click on the top image in this article to see more delicious corporate jargon from tronc HR.)

TL;DR: Video, like text before it, is about to explode in supply, and prices are eventually going to drop because much of that video inventory is going to be terrible. We will exaggerate that supply with metrics that aren’t real, which will obscure the fact that the ones that are real aren’t rising as quickly as we’d expected or declining as quickly as we’d hoped. Best of all, we’ll make room for our mediocre new video supply – as we already are – by reducing the supply of text content: you know, that thing that was the Future of News a few months ago.

One can only hope that, by the time the video market has plateaued, the news media will have found the next future of news monetization. They’re going to need it.

That’s not the fault of Facebook: it’s only a problem for journalists. Here’s the unfortunate truth about good journalism: it’s inherently non-scalable. The principles that work so well in tech companies – especially ones like Facebook that operate in two-sided markets and that benefit enormously from network effects – are worth very little to journalism, at least in immediate terms. Producing 2,000 AI-assisted videos will contribute virtually nothing to the corpus of quality content, while doing much to dilute the market for everyone who’s actually creating some.

One of my favorite writers on tech and media, Ben Thompson, appeared on Ezra Klein’s podcast in April. During the episode, Klein asked him how he was able to successfully find and keep a (paying) audience online. Although he raised other factors too, Thompson summarized his approach thusly: “You just have to produce stuff that’s really good.”

That’s the whole secret. It may not be the answer journalists want, but it’s the only one they’ve got.